Less than a year ago, we reported extensively on the construction of the foundations for ‘bridge 9’, the new bridge on the south side of the Schinkelbrug. The foundations – 18 m long poles – were lifted into the water from a pontoon. At that time, very little of the future bridge was visible (except underwater), but things are very different less than a year later. Anyone cycling, driving or sailing past cannot fail to see it: the concrete columns that will soon be supporting the bridge are now clearly protruding from the water.

Gearbox

In recent months, the TriAX construction consortium (Besix, Dura Vermeer and Heijmans) has been hard at work on the two supports (see the timelapse video above). The construction work has mainly involved applying formwork, reinforcement and pouring concrete. In addition, TriAX is focusing on construction work on the bascule cellar for bridge 9. This is very intricate work, says Sander Wedershoven. He is chief planning engineer for the Schinkelbrug. ‘In this cellar, there will be hinges that allow the bridge to open and close. It’s all made up of huge numbers of components that link together with millimetre precision. It’s like one big gearbox under the influence of some very strong forces.’

Panama wheel weighing 30 tonnes

The cellar is where we will ultimately be fitting the operating mechanism for the bridge. ‘Many of these components are currently being pre-built – they include a 3 m high wheel that is being produced in France’, says Wedershoven. ‘You do realise, that so-called Panama wheel weighs 30 tonnes. And when the operating mechanism has been fitted, we’ll lift the steel leaf, weighing 300 tonnes, into place. That is the moving part of the bridge that is currently being pre-built in Friesland and that we are transporting to the Schinkelbrug by water.’

Lifting in the girders

Even after the steel leaf has been lifted into position, the bridge will be nowhere near complete. On top of the supports, we will be adding huge concrete beams (girders) that will then be welded together. There will be a sheet of concrete on top of that. ‘In order to lift those girders into position – there are around 28 in total – we will need to close the A10 Zuid in early 2026. Even when the whole bridge has been completed, we will still need to do the finishing work on it all.’ Bridge 9 will need to be operational by 2027. In other words: the bridge can then be used to take traffic from bridge 10 across it.

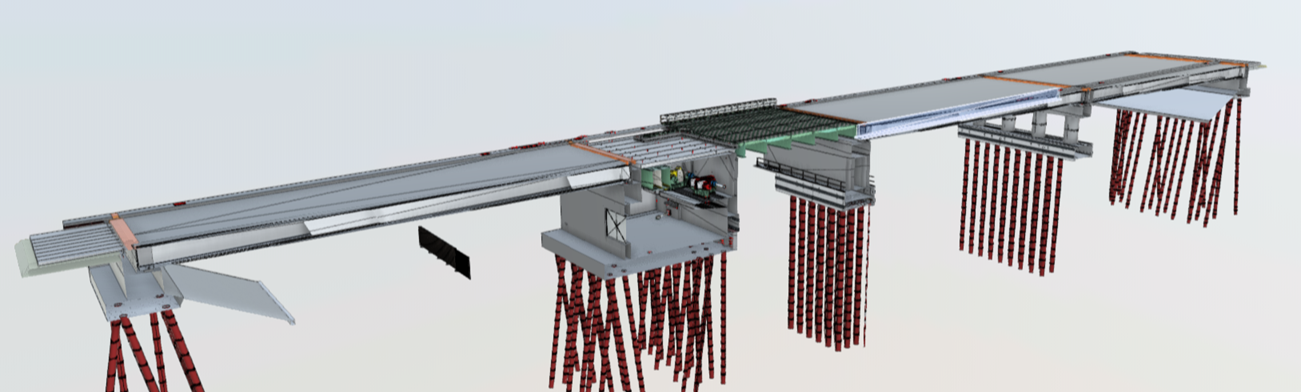

A schematic representation of bridge 9. The abutments are at the ends on the right and left. The bridge rests on the bascule cellar (left) and the two supports. The steel leaf is on the left side.

Preventing bridge collisions

Recent building work has not been confined to the bridge itself. A gigantic steel structure has been installed in the water just before the bridge. ‘We started by putting large piles in place there. On top of that, we fitted a prefabricated frame. That’s how you build a fender system’, explains Wedershoven. ‘The structure is designed to protect the bridge from collisions. It’s like a collision absorber: if needed, it’s actually capable of turning round the most heavily laden ship to prevent it crashing through the bridge.’

Widening of A10 Zuid

The construction of four new bascule bridges for road traffic is part of the reconstruction of the De Nieuwe Meer junction. This is needed to be able to widen the A10 Zuid by adding two extra lanes for local traffic. The new northern bridge (1) and southern bridge (9) will be the first to be used from mid-2027. From then on, the southern bridge will serve as a bypass for traffic on the existing southern A10 bridge (10). This will ultimately be demolished and replaced by two new bridges (7 and 8). The Schinkelbrug is scheduled for completion in 2031.

Share article:

Give your opinion

Get in touch with us